When I was a child, I had no concept of gender. I was, in all meanings of the word, free. I played with whatever toys I wanted to, imagined myself as whatever I wanted, galivanting around without a care in the world. My head was so far in the clouds it barely felt the pull of gravity. I had had a few interactions with other children at daycare or on the playground that made me very aware of the gender I was assigned at birth. They would regurgitate their parent’s ideas without even knowing what they meant.

“Girls can’t be firefighters!!” a classmate told me as we sat underneath the dirty green slide on the second day of daycare. I simply proclaimed he was wrong and went on with my day. As much as this kid had no understanding of what he had just said, I had no understanding of what was just said to me. As I got closer to middle school, I got older, and so did my body. Suddenly every part of me was subjected to scrutiny, my features commodities to be criticized and dissected. The world looked at me, and that made me aware of myself for the first time.

I felt wrong. My skin felt too tight in some places, too loose in others. Parts of me became concave and convex in places I wasn’t before. But I was told that was part of growing up. Your body changes, and it’s uncomfortable but normal. I thought it was normal, so I ignored it. When I entered middle school, my skin seemed to shrink even more, trapping me. With every passing day, I found myself hating more and more aspects of myself. The way clothes looked on me, the way my voice sounded in recordings, the way others would perceive me.

This was all further complicated by my experience as a Mexican person and the way being visibly Mexican has shaped the way people in the United States see me, and in turn the way I see myself. For most of my young life I have felt ugly. Not just because I was dealing with dysphoria and didn’t know, but because the country I lived in told me so. I grew up never seeing anyone with my skin color or body type. I would come home from school crying because I didn’t have blue eyes and blond hair. White actresses on TV convinced me I was ugly for not looking like them, so it was so easy to write off my bodily discomfort as being self-conscious. As just being a teenager.

It was so much more than that though. By the time I entered high school I knew I wasn’t a girl. Even then, however, it took a lot of introspection to allow myself to fully accept myself. I told my parents, and it took them a bit to understand but they were supportive all throughout. I started my social transition the summer between my Junior and Senior year of high school, and that November I started my hormone replacement treatment.

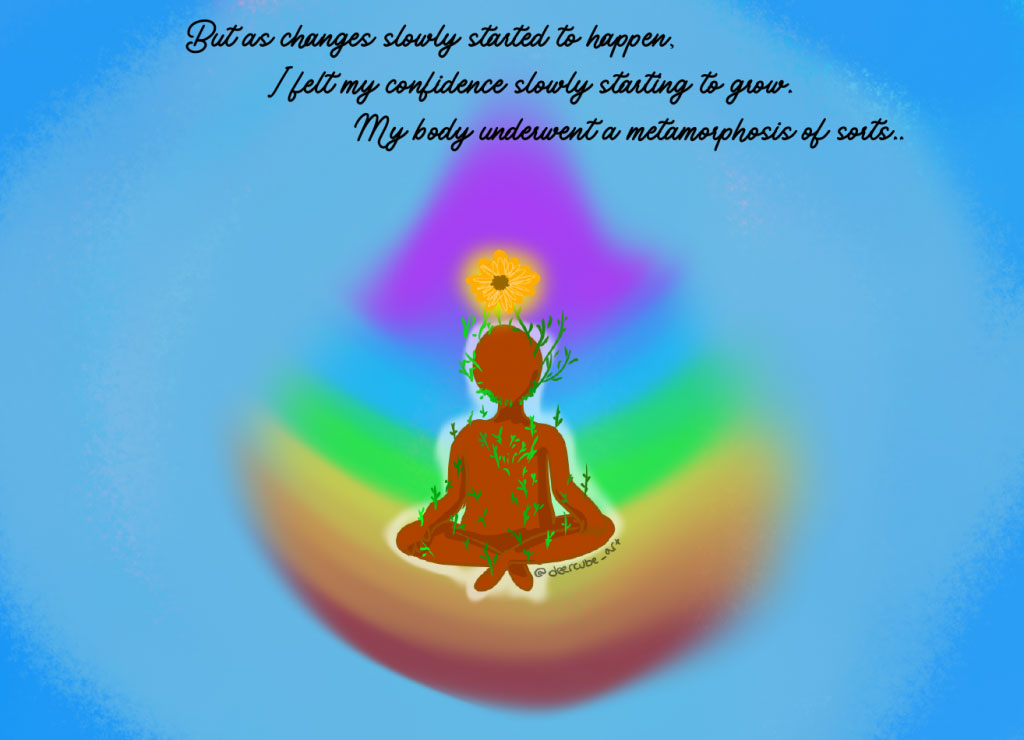

At first, I didn’t feel much of a difference, and I thought that this was an indicator that I had made a mistake. That I wasn’t actually transgender. But as changes slowly started to happen, I felt my confidence slowly starting to grow. My body underwent a metamorphosis of sorts, the hormones in my system altering my shape. The fat in my body redistributed, my voice deepened, and my hair follicles produced hair at a rapid pace. And this is when I realized that my issues with my body that I could date back to childhood had always been dysphoria in disguise. I would look at myself in the mirror and see me for the first time since I was a genderless child under the slide. I boiled down to me not actually hating my features, but hating my features being perceived as feminine. I still have a long way to go, but every day it gets a little bit easier.